motorbike

Driving school

theory book

to category A

Chapter 5: Technical driving conditions and technical driving equipment

The manoeuvres you learned in the closed practice area (chapter 2) were designed to get to know the motorcycle. And to give you a sense of the motorcycle's centre of gravity and balance points. The manoeuvres in traffic (chapter 4) were designed to teach you how to function as part of the overall traffic situation. You should practise some routine situations and generally become more familiar with the motorcycle. This chapter prepares you for manoeuvres on a driving school. At such a facility, you have the opportunity to experiment with some driving conditions and physical laws of nature. You don't do these kinds of experiments in traffic. But they are important to learn. Should you find yourself in a critical situation, you can more easily avoid accidents and mishaps if you are prepared for how the motorbike reacts. At the driving school, you need to practise critical situations. This means, for example, braking on a short stretch of road and braking and evasive manoeuvres. You also need to know how speed affects your chances of completing an evasive manoeuvre. Finally, you need to know why a motorbike reacts the way it does. This way, you can avoid the panic braking that often ends badly. These exercises are done on a solo motorbike. The motorcycle licence entitles you to drive with a sidecar and trailer. Therefore, you will also need to complete a few exercises on a motorbike with a sidecar. You do not need to complete exercises in driving with a trailer.

Speed and braking distance

The motorbike's propulsion is due to the power developed in the engine. When the motorbike is moving, it has a certain amount of kinetic energy. This kinetic energy means that the motorbike will continue to move some distance after you have switched off the engine. Or after you have disconnected the engine from the rear wheel by pulling the clutch lever down or after you have put the motorcycle in neutral. The faster the motorbike is travelling, the more kinetic energy it has. If the speed doubles, the kinetic energy quadruples. If the speed triples, the kinetic energy increases ninefold. So if you slow down a little, the distance the motorbike can travel on kinetic energy is shortened. In terms of braking distance, the same maths applies. If the kinetic energy doubles, the braking distance quadruples. And if the kinetic energy triples, the braking distance increases ninefold. That is, if you brake with exactly the same force. It doesn't take a genius to figure out that just driving a few kilometres per hour faster increases the braking distance by a relatively large amount.

Brake lengths

From the moment you start braking until the motorbike comes to a complete stop at a standstill, you will have travelled a distance. This distance is called the braking distance. The braking distance depends on the braking technique you use. The shortest braking distance is achieved by using both brakes at the same time and just hard enough that the wheels almost lock up. You can practise this technique at the technical driving centre. You can check it yourself, how braking distances change in relation to speed. For example is the braking distance at 60 km/h.

- Approx. 50 metres with soft braking.

- Approximately 30 metres during heavy braking.

- Approx. 20 metres under very hard braking.

You'll also find that braking distance almost doubles, as long as you drive a little faster. For example, braking distance doubles if you increases speed from 30 km/h. to 40 km/h. Braking distance also depends on the amount of grip and the road surface. Imagine you want a maximum braking distance of 35 metres. This means, that you can drive 80 km/h on a level, dry road. To maintain braking distance, you can only drive 60 km/h. on wet tarmac or gravel. If you are driving on packed snow, you must reduce your speed to 40 km/h, and if it is icy, you must you can go as low as 30 km/h. When travelling downhill, the longer the braking distance, the steeper the hill is.

20 metres

30 metres

50 metres

Legal requirements for brakes

§ As you probably remember, the law states that with or without loading, the brakes must be able to stop the motorcycle safely, quickly and effectively. In other words, this means that the braking distance at 30 km/h when using both brakes must not exceed 7 m. If you only use the front wheel brake, the braking distance must not exceed 9 m.

And if you only use the rear wheel brake, the braking distance must not exceed 11 m.

The grip

Traction refers to both the friction between the tyre and the road surface, but it also means that the tyres grip and bounce off uneven road surfaces. Traction is necessary for the engine's power to turn into acceleration and for you to brake and steer.

The design of a motorbike makes it more sensitive to reduced traction than a car, for example. If you ride in wet and greasy conditions, or on rocks and sand, it's harder to stop and the risk of a crash increases. You need to be very careful when using the throttle, clutch, brakes and steering. And, of course, be extra careful not to drive too fast.

Loading, tyre pressure and tread pattern

Driving with passengers or heavy loads on the back increases the pressure on the rear tyre - and therefore relieves the pressure on the front tyre. This means that the front tyre's grip can be reduced to the point where it makes it harder for you to steer. It also makes the motorbike more sensitive to crosswinds. When you start and accelerate, the weight shift between the front and rear tyres increases. The weight shift can be counteracted slightly by having the passenger lean forwards with you.

Tyre pressure also has an impact on grip. Grip - and therefore the ability to steer safely - is reduced if there is too much or too little air in the tyres. Most motorcycles have a long groove pattern on the front tyre and a cross groove pattern on the rear tyre. A worn tyre tread pattern greatly reduces grip in the wet. As you know, the tread should be at least 1 mm deep, but there's absolutely no reason to wait that long to change your tyres. As a rule of thumb, you should change your tyres when the tread is 3mm deep.

Traction utilisation

When braking on a slippery road where grip is reduced, there is a risk of the wheels locking. The correct way to brake here is to apply the brake pedal lightly and pull the handbrake lever very lightly. If the wheels lock, the braking distance will be much longer and there is a greater risk of the motorbike skidding and tipping over. If you're travelling through a corner with reduced traction, avoid even the slightest acceleration or softest braking. This also increases the risk of skidding and thus a crash. The same applies during an evasive manoeuvre. It is simply poor and extremely dangerous driving technique to brake and steer at the same time.

Front or rear wheel skidding

If you brake so hard that one or both wheels lock up, it's difficult keeping your balance on the motorbike. You will usually skid, and if If you're not very fast and skilful, you'll fall over too. As soon as you notice that the motorbike is slipping, let go of the apply the brakes and disengage the clutch until you have straightened the bike. You can then accelerate again and slowly release the clutch lever. With the This method utilises traction to steer. During a skid, never try to accelerate or brake, this will only make the skid worse.

Cornering and the racing line

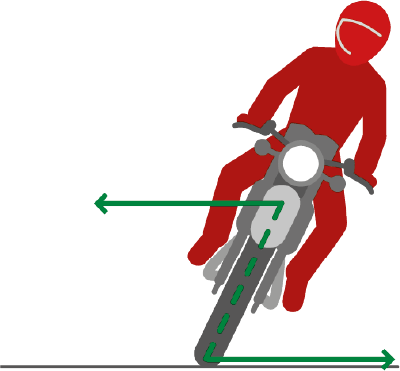

Centrifugal force is a law of physics. When you go through a corner, centrifugal force will try to pull the motorbike out of the corner. You counteract the force by leaning the motorbike to the opposite side.

The centrifugal force becomes stronger the faster you drive and the sharper the turn. If the speed doubles, the centrifugal force quadruples. If the speed triples, the centrifugal force increases ninefold. If the curve radius of the turn is halved (i.e. the turn becomes sharper), the centrifugal force doubles. Conversely, if the curve radius of the swing doubles, the centrifugal force will halve. Therefore, you should always try to flatten the turn and drive in the line called the ideal line. If the centrifugal force becomes stronger than the road grip, the motorbike will skid and most likely roll over.

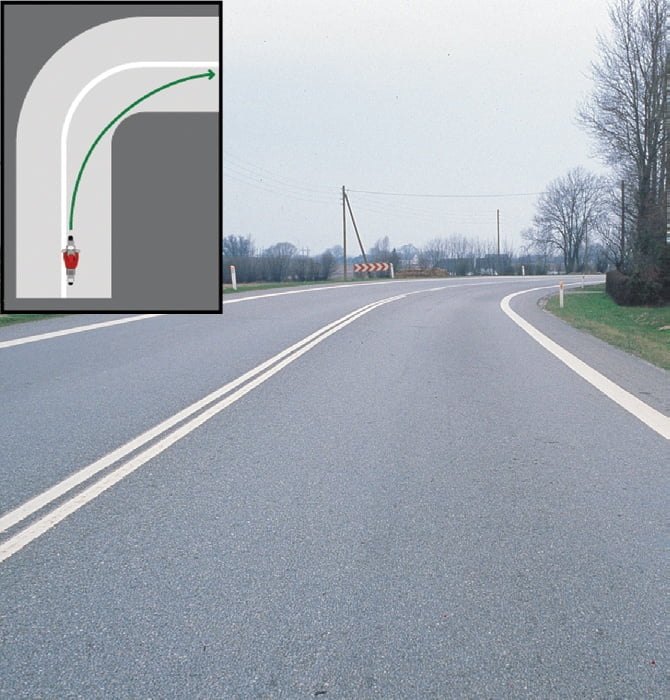

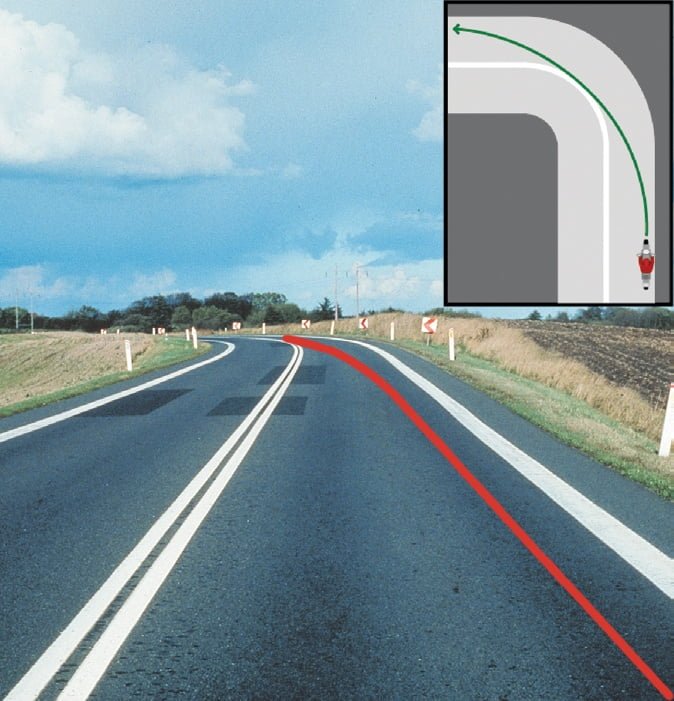

Travelling in the ideal line means that you make the line you're travelling in as flat as possible. This means that the radius of the curve becomes larger and the centrifugal force smaller. When making a right turn, pull out towards the centre of the road. As soon as you can see through the corner, pull in towards the apex of the curve and exit the corner in the centre of your lane.

When making a left turn, pull out to the right edge of the road. When you can see through the corner, pull towards the apex in the centre of the road and exit the corner in the middle of your own lane. Even before you enter the corner, you need to find a suitable speed to drive through the corner. In other words, you don't accelerate or brake in a corner.

You also need to be careful not to enter a corner too early. If you do, you'll be forced to correct your steering and there's a high risk of pulling into the opposite lane.

Shaking and vibrations in the motorbike

Shimmy, wobble and wobble are some words for the shaking that can suddenly occur in your motorbike when you ride. Shimmy is when the front wheel or front suspension vibrates violently and continuously. This happens at 60-80 km/h. This can be caused by tyre wear, an imbalance in the front wheel or telescopes. It can also be due to loose fork bridges or play in the head tube bearings. Wobble comes suddenly - and especially at high speed - and causes the entire motorbike to wobble or shake. It may be caused by passing a bumpy section of road, but it can also be caused by the rigidity of the frame, the motorcycle's equipment or its load, including your own body weight. If you experience wobbling, immediately lean forwards. Once the wobble has stopped, slow down by releasing the throttle. You can then straighten up again and continue driving. Wiev is an oscillation of the motorbike that you would normally only experience when travelling very fast. Wiev can be caused by a torsional stiffness in the frame, possibly in combination with play at the suspension. It can also be caused by loading, including your body weight, and incorrect or bad tyres.

Exercises at the driving school

At the driving centre, you will try out the driving techniques and conditions you have learnt about in the first part of this chapter. By reading this section, you are prepared for the exercises you will complete under the guidance of your instructor. For some of the exercises, your instructor will need to accompany you as a passenger.

You will complete exercises both on a solo motorbike and on a motorbike with a sidecar, for example.

1) Braking distances at different brake forces and speeds. At 60 km/h, practise stopping the motorcycle at 50 m, 30 m and 20 m respectively.

2) Braking while travelling straight ahead. You must stop at a marked destination. For each exercise, the speed is increased to eventually reach 70 km/h. Then you must brake in the shortest possible braking distance, also at a speed of up to 70 km/h. You need to learn to disengage and use both brakes. Once you're confident, your instructor should come along as a passenger.

3) Slalom driving and counter-steering. At 40-50 km/h, slalom around at least 6 cones at a distance of at least 20 metres. Then complete the exercise with rhythmic counter-steering. Counter-steering means that you start steering by turning the handlebars in the opposite direction you want to go. For example, if you want to avoid going right, you first turn the handlebars to the left. Counter-steering prepares you for the avoidance manoeuvre.

4) You need to learn how to find the ideal line in a turn. First with markings and later without. You need to enter the corner from both the right and the left. Later, you will need your instructor as a passenger.

5) Braking with evasive manoeuvres. You need to learn how to declutch, brake with both brakes, release the brake and counter-steer around an obstacle. This is an important exercise! Get good at it and then try a double avoidance exercise.

Driving with a sidecar

Once you've familiarised yourself with the solo motorcycle, you'll have to forget most of that technique for a short while, because now it's time to try riding a motorcycle with a sidecar.

A motorbike with a sidecar is a "leaning" vehicle and this affects the steering when starting, accelerating, braking and cornering. For example, you can't lean a motorbike with a sidecar in a corner. You have to turn the handlebars during the turn, which can be a heavy task. When you start or accelerate, the vehicle tends to pull to the right due to the heavy sidecar. When braking or decelerating, the vehicle tends to pull to the left due to the kinetic energy of the sidecar. If the sidecar has brakes, it will pull less to the left. If the vehicle is heavily loaded or the sidecar has a long load, the steering will be even more affected by the sidecar. The slower you drive, the more you are in control. A sidecar can be designed for either goods or passenger transport. On a goods sidecar, its total weight and load must be written on the side. A passenger sidecar may only transport the number of

persons it is approved for plus one child under the age of 10. And here the obligation to wear a helmet also applies.

Even a soft right turn, such as during an overtaking manoeuvre, can be enough to cause the sidecar to lift. If you drive too fast in a left turn, the rear tyre will tend to lift off. You can counteract this by leaning backwards to the left. If the rear tyre lifts, shut off the throttle immediately and steer towards the sidecar. If you brake before the motorbike is upright, there is a high risk of tipping over. It doesn't take much speed to tip over during this exercise.

Exercises with sidecar

At the driving centre, you will experience how a motorcycle with a sidecar is different from a solo motorcycle. You will try different steering, acceleration and braking exercises.

1) Driving in eights around two cones that are as close to each other as possible.

2) Slalom between at least 9 cones with progressively decreasing distance.

3) Acceleration and braking. At 70 km/h, stop at a marked target using both brakes. You choose the braking force and time. Then brake with the shortest possible braking distance with gradually increasing speed up to 70 km/h.

4) You drive in a circle and increase speed until the sidecar wheel lifts off the road.

5) Swinging from right to left.

The exercises at the driving centre are a final polishing of your new skills. And you should now be ready to drive! Are you? In the next chapter, you can read about what to expect in the theory and practical tests.

Test your knowledge

Cat. A - Section 5

Select the questions you think are the right ones.